Denmark Abolishes All Corona Measures

Tight Hip Flexors - most neglected muscle in the body

Risky Play - Why Children Love it and Need it

Washington Post Article on Posture

How can Chiropractors benefit your health?

Danish parliament recently decided in Copenhagen that all Corona measures should be ended from October 1. There will therefore no longer be a mask requirement and the test regime will be abolished. The Danes will then no longer have to provide evidence of whether they are vaccinated or unvaccinated, or whether they have tested positive or negative.

All Corona measures are being lifted in view of the increasing incidence figures in Denmark, reported RT Deutsch. Since the beginning of July this value has risen from 31 to 107,2 (as of August 8). At the same time, the upper limits of this Corona indicator has increased significantly.

At the same time, the incidence limits are increased significantly: In communities from 300 to 500 infected people within seven days, in the districts from 500 to 1000. However, the prerequisite is that an increasing number of Covid-19 patients does not overload the health care system.

Denmark’s SSI infectious diseases agency said it no longer relied on vaccination to achieve herd immunity in the country. Tyra Grove Krause, the SSI’s acting academic director, said a new wave of infections were expected after people return to work and school at the end of this summer, but it should not be cause for alarm. “It will be more reminiscent of the flu,” Krause said.

Overall, the current vaccination rate is just under 58,4 percent of fully vaccinated people in Denmark. In Germany, this value is only slightly lower at 54,5 percent (as of August 8) but vaccine advocates have been persistent in their fear-mongering and pressure on the unvaccinated.

Tyrolean lawyer Dr. Renate Holzeisen, meanwhile strongly recommended that all employers refrain from vaccination pressure or compulsory vaccination, because most of them were “obviously not even aware of the far-reaching legal consequences associated with it”.

The fact that the so-called Covid-19 vaccines, according to the official approval documents of the EMA and the European Commission were not developed and approved for the prevention of infection with the SARS-COV-2 virus, but solely to prevent a more severe course of the disease, were conditionally approved for this reason alone, Holzeisen underscored.

The official approval documents therefore show that these substances cannot interrupt the chain of infection because the people treated with them can become infected and thus be infectious. Practice also proves that people who are completely “vaccinated” become infected with the virus and even have the same viral load as “unvaccinated people” as the CDC, among others, has admitted. It is therefore clear that any Covid-19 “compulsory vaccination” actually lacks any justification.

HOW TIGHT HIPS CAN HOLD YOU BACK…

Many people don’t realize that the root cause of some of their pain and other health problems might be tight hip flexors.

The impact the hips have on the whole body never occurred to me until I saw the effect tight hip flexors had on the health and well-being of my wife after she gave birth.

It was only then that I truly understood the magnitude of the problem.

Tight or locked hip flexors can contribute to the following problems:

Nagging joint pain in the legs, lower back or hips [19-26][29]

Walking with discomfort [19-27][29]

Hips locking up [29]

Bad posture [27]

Trouble sleeping [30]

Sluggishness in day to day life [31]

High anxiety [32]

Lack of explosiveness in the gym or sports [33][49-54]

Do you find it surprising that all of this might be simply caused by this one tight muscle?

Many people suffer from tight or locked hip flexors, especially those who sit for hours each day, but few realize the impact on your whole body.

Again, everything flows through the hips.

They help to support the strength and health of your entire body.

AND AT THE VERY HEART OF THIS IS THAT POWERFUL SURVIVAL MUSCLE – HIP FLEXORS

HIP FLEXORS ARE THE BODY'S MOST POWERFUL, PRIMAL MUSCLE… THAT YOU'VE NEVER TRAINED

RISKY PLAY

AUTHOR // Peter Gray, Ph.D.

Why Children Love It and Need It.

To protect our children we must allow them to play and learn without adult supervision.

Fear, you would think, is a negative experience, to be avoided whenever possible. Yet as everyone who has a child or once was one knows, children love to play in risky ways—ways that combine the joy of freedom with just the right measure of fear to produce the exhilarating blend known as thrill.

Six categories of risky play

Ellen Sandseter, a professor at Queen Maud University in Trondheim, Norway, has identified six categories of risks that seem to attract children everywhere in their play. These are:

Great heights. Children climb trees and other structures to scary heights, from which they gain a bird’s-eye view of the world and the thrilling feeling of “I did it!”

Rapid speeds. Children swing on vines, ropes or playground swings; slide on sleds, skis, skates or playground slides; shoot down rapids on logs or boats; and ride bikes, skateboards and other devices fast enough to produce the thrill of almost but not quite losing control.

Dangerous tools. Depending on the culture, children play with knives, bows and arrows, farm machinery (where work and play combine) or other tools known to be potentially dangerous. There is, of course, great satisfaction in being trusted to handle such tools, but there is also thrill in controlling them, knowing that a mistake could hurt.

Dangerous elements. Children love to play with fire, or in and around deep bodies of water, either of which poses some danger.

Rough-and-tumble. Children everywhere chase one another around and fight playfully, and they typically prefer being in the most vulnerable position— the one being chased, or the one underneath in wrestling—the position that involves the most risk of being hurt and requires the most skill to overcome.

Disappearing/getting lost. Little children play hide and seek and experience the thrill of temporary, scary separation from their companions. Older ones venture off on their own, away from adults, into territories that to them are new and filled with imagined dangers, including the danger of getting lost.

The evolutionary value of risky play

Other young mammals also enjoy risky play. Goat kids frolic along steep slopes and leap awkwardly into the air in ways that make landing difficult. Young monkeys playfully swing from branch to branch in trees, far enough apart to challenge their skill and high enough up that a fall could hurt. Young chimpanzees enjoy dropping from high branches and catching themselves on lower ones just before hitting the ground. Young mammals of most species, not just ours, spend great amounts of time chasing one another around and play fighting—and they, too, generally prefer the most vulnerable positions.

From an evolutionary perspective, the obvious question about risky play is this: Why does it exist? It can cause injury (although serious injury is rare) and even (very rarely) death, so why hasn’t natural selection weeded it out? The fact that it hasn’t been weeded out is evidence that the benefits must outweigh the risks. What are the benefits? Laboratory studies with animals give us some clues.

Researchers have devised ways to deprive young rats of play during a critical phase of their development without depriving them of other social experiences. Rats raised in this way grow up emotionally crippled. When placed in a novel environment, they overact with fear and fail to adapt and explore as a normal rat would. When placed with an unfamiliar peer, they may alternate between freezing in fear and lashing out with inappropriate, ineffective aggression. In earlier experiments, similar findings occurred when young monkeys were deprived of play (though the controls in those experiments were not as good as in the subsequent rat experiments).

Such findings have contributed to the emotion regulation theory of play—the theory that one of play’s major functions is to teach young mammals how to regulate fear and anger. In risky play, youngsters dose themselves with manageable quantities of fear and practice keeping their heads and behaving adaptively while experiencing that fear. They learn that they can manage their fear, overcome it, and come out alive. In roughand- tumble play they may also experience anger, as one player may accidentally hurt another. But to continue playing, to continue the fun, they must overcome that anger. If they lash out, the play is over. Thus, according to the emotion regulation theory, play is, among other things, the way that young mammals learn to control their fear and anger so they can encounter real-life dangers, and interact in close quarters with others, without succumbing to negative emotions.

The harmful consequences of play deprivation

On the basis of such research, Sandseter wrote, in a 2011 article in the journal Evolutionary Psychology, “We may observe an increased neuroticism or psychopathology in society if children are hindered from partaking in age-adequate risky play.” She wrote this as if it were a prediction for the future, but I’ve reviewed data— in Free to Learn and elsewhere—indicating that this future is here already and has been for a while.

Briefly, the evidence is this: Over the past 60 years we have witnessed in our culture a continuous, gradual, but ultimately dramatic decline in children’s opportunities to play freely, without adult control, and especially in their opportunities to play in risky ways. Over the same 60 years we have also witnessed a continuous, gradual, but ultimately dramatic increase in all sorts of childhood mental disorders, especially emotional disorders.

Look back at that list of six categories of risky play. In the 1950s, even young children regularly played in all of these ways, and adults expected and permitted such play (even if they weren’t always happy about it). Now parents who allowed such play would likely be accused of negligence, by their neighbors if not by state authorities.

Here—as an admittedly nostalgic digression—are just a few examples of my own play, as a child in the 1950s:

At the age of 5, I took bike rides with my 6-year-old friend all over the village where I lived and into the surrounding countryside. Our parents gave us some limits as to when we had to be back, but they didn’t restrict our range of movement. (And, of course, we had no cell phones then, no means of contacting anyone if we got lost or hurt.)

From the age of 6 on, I, and all the other boys I knew, carried a jackknife. We used it not just for whittling, but also for games that involved throwing knives (never at each other).

At age 8, I recall, my friends and I spent recesses and lunch hours wrestling in the snow or grass on a steep bank near the school. We had tournaments that we arranged ourselves. No teachers or other adults paid attention to our wrestling, or, if they did, they never interfered.

When I was 10 and 11, my friends and I took all-day skating and skiing hikes on the 5-mile-long lake that bordered our northern Minnesota village. We carried matches and occasionally stopped on islands to build fires and warm ourselves, as we pretended to be brave explorers.

Also when I was 10 and 11, I was allowed to operate the big, dangerous, hand-fed printing press at the print shop where my parents worked. In fact, I often took Thursdays off from school (in fifth and sixth grades), to print the town’s weekly newspaper. The teachers and principal never complained, at least not that I know of. I think they knew that I was learning more valuable lessons at the print shop than I would have at school.

Such behavior was unexceptional in the 1950s. My parents may have been a bit more trusting and tolerant than most other parents, but not by much. How much of this would be acceptable to most parents and other adult authorities today? Here’s an index of how far we have moved: In a recent survey of more than a thousand parents in the United Kingdom, 43 percent believed that children under the age of 14 shouldn’t be allowed outside unsupervised, and half of those believed they shouldn’t be allowed such freedom until at least 16 years of age! My guess is that roughly the same would be found if that survey were conducted in the United States. Adventures that used to be normal for 6-year-olds are now not allowed even for many teenagers.

As I said, over the same period that we have seen such a dramatic decline in children’s freedom to play, and especially in their freedom to embrace risk, we have seen an equally dramatic rise in all sorts of childhood mental disorders. The best evidence for this comes from the analyses of scores on standard clinical assessment questionnaires that have been given in unchanged form to normative groups of children and young adults over the decades. Such analyses reveal that five to eight times as many young people today suffer from clinically significant levels of anxiety and depression, by today’s standards, than was true in the 1950s. Just as the decline in children’s freedom to embrace risk has been continuous and gradual, so has the rise in children’s psychopathology.

The story is both ironic and tragic. We deprive children of free, risky play, ostensibly to protect them from danger, but in the process we set them up for mental breakdowns. Children are designed by nature to teach themselves emotional resilience by playing in risky, emotion-inducing ways. In the long run, we endanger them far more by preventing such play than by allowing it. And, we deprive them of fun.

Free-form play is safer than supervised sports

Children are highly motivated to play in risky ways, but they are also very good at knowing their own capacities and avoiding risks they are not ready to take, either physically or emotionally. Our children know far better than we do what they are ready for. When adults pressure or even encourage children to take risks they aren’t ready for, the result may be trauma, not thrill. There are big differences among kids, even among those who are similar in age, size and strength. What is thrilling for one is traumatic for another. When physical education instructors require all of the children in a gym class to climb a rope or pole to the ceiling, some children, for whom the challenge is too great, experience trauma and shame. Instead of helping them learn to climb and experience heights, the experience turns them forever away from such adventures. Children know how to dose themselves with just the right amount of fear for them, and for that knowledge to operate they must be in charge of their own play. (Parenthetically, I note that a relatively small percentage of children are prone to overestimate their abilities and do repeatedly hurt themselves in risky play. These children may need help in learning restraint.)

An ironic fact is that children are far more likely to injure themselves in adult-directed sports than in their own freely chosen, self-directed play. That’s because the adult encouragement and competitive nature of the sports lead children to take risks— both of hurting themselves and of hurting others—that they would not choose to take in free play. It is also because they are encouraged, in such sports, to specialize, and therefore overuse specific muscles and joints. According to the latest data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 3.5 million children per year under the age of 14 receive medical treatment for sports injuries. That’s about 1 out of every 7 children engaged in youth sports. Sports medicine for children has become a big business, thanks to adults who encourage young pitchers to throw so hard and so often they throw out their elbows, encourage young football linemen to hit so hard they get concussions, encourage young swimmers to practice so often and hard they damage their shoulders to the point of needing surgery. Children playing for fun rarely specialize (they enjoy variety in play), and they stop when it hurts, or they change the way they are playing. Also, because it’s all for fun, they take care not to hurt their playmates. Adults, who get all wrapped up in winning and may hope for eventual scholarships, work against nature’s means of preventing damage.

So, we prevent children from their own, self-chosen, thrilling play, believing it dangerous when in fact it is not so dangerous and has benefits that outweigh the dangers, and then we encourage children to specialize in a competitive sport, where the dangers of injury are really quite large. It’s time to reexamine our priorities.

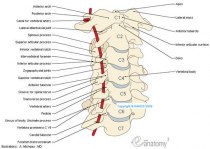

So how do the Three T’s cause subluxation and affect the function of the nervous system as a whole? First of all, let’s consider the area of trauma, specifically physical trauma, as a cause. It is easy to understand how a vertebra can become misaligned as a result of physical trauma to the spine—forceful birthing procedures that pull and twist a baby’s head to expedite the delivery process, falls endured while learning how to walk, playground injuries, or even bad posture. The body will logically try to stabilize this area with muscle splinting, which will heal in this configuration unless something is done to restore integrity to the area.

However, apart from direct force causing a bone to misalign, the body can be affected by chemical exposure and emotional stresses in such a way as to cause subluxations. The nervous system perceives these non-physical stressors to be threatening and directs the muscles to react, defend and brace the body, holding bones in positions that can cause asymmetry and imbalance in the spine. No muscle moves a bone without a nerve purposefully telling it to do so. Realize that the vertebrae never move without a muscle pulling them. These misalignments and alterations in spinal curvature are only a result of the internal, neurological response to the overwhelming presence of the Three T’s.

Click Here to read the rest.

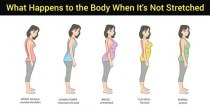

We know sitting too much is bad, and most of us intuitively feel a little guilty after a long TV binge. But what exactly goes wrong in our bodies when we park ourselves for nearly eight hours per day, the average for a U.S. adult? Many things, say four experts, who detailed a chain of problems from head to toe.

STRAINED NECK If most of your sitting occurs at a desk at work, craning your neck forward toward a keyboard or tilting your head to cradle a phone while typing can strain the cervical vertebrae and lead to permanent imbalances. SORE SHOULDERS AND BACK The neck doesn't slouch alone. Slumping forward overextends the shoulder and back muscles as well, particularly the trapezius, which connects the neck and shoulders. Bad back INFLEXIBLE SPINE When we move around, soft discs between vertebrae expand and contract like sponges, soaking up fresh blood and nutrients. But when we sit for a long time, discs are squashed unevenly. Collagen hardens around supporting tendons and ligaments. DISK DAMAGE People who sit more are at greater risk for herniated lumbar disks. A muscle called the psoas travels through the abdominal cavity and, when it tightens, pulls the upper lumbar spine forward. Upper-body weight rests entirely on the ischial tuberosity (sitting bones) instead of being distributed along the arch of the spine. To read entire article, please click on the link above the illustration.

The research about chiropractic care is growing. According to the Annals of Internal Medicine, recent studies show that spinal manipulative therapy performed by a chiropractor, along with exercise, relieve neck pain more effectively than medication.

Furthermore, the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics reported that an integrated approach to health care -- including chiropractic care -- results in a 51.8 percent reduction in pharmaceutical costs and 43 percent fewer hospital admissions.

You should consider seeing a chiropractor if you experience frequent pain in your back, neck or joints, as well as headaches. This is especially so if intense soreness follows accidents, household chores or prolonged periods of poor posture.

Letter to The Washington Post

January 07, 2014

To the Editor:

“How safe are the vigorous neck manipulations done by chiropractors?” attempted to shed light on the importance of shared decision making between a doctor and his or her patient—a standard that should apply to every treatment regardless of the provider.

Chiropractic services have outperformed all other spinal pain treatments, including prescription pain medication, according to national consumer satisfaction surveys, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has classified prescription pain medication abuse as an epidemic in the United States. Any treatment in health care has its risks; however cervical manipulation is far safer than other more invasive procedures.

As a result, approximately 27 million people in the U.S. seek the care of a doctor of chiropractic (DC) each year. DCs have doctoral-level graduate training in diagnosis and treatment. Professional standards dictate employing best efforts that enable patients to make informed choices regarding proposed treatment. DCs rely on the largest research study, which determined there is no cause-and-effect relation between neck manipulation and cervical artery dissection leading to stroke.

Let’s focus on patient-centered, integrated treatment options that improve the quality and safety of spinal pain management.

Keith Overland, DC

President, American Chiropractic Association

Visit the ACA's website for more patient information or read the research study mentioned in the letter by clicking the links above the illustration.